Macroeconomics is a funny thing. About 80 years ago, on the heels of our earlier depression, I wrote a book. It seemed as though people enjoyed The General Theory well enough, since the the ideas I described in it — along with some very silly ones that I disproved — became rather popular in the years that followed. Then, to my great disappointment — roughly around the time of a couple garish trends called "disco" and the "Rubik's Cube" — it seems my book became an embarrassment to certain Chicago raconteurs. Dispiritingly, as culture slid further toward "synthesized keyboards" and "supply-side economics", so too did my ideas retreat deeper into the abyss.

Class, this folderol ends today. The fates of money supplies, unemployed lads, and comatose economies mean too much to me to let this nonsense go unchecked. Books out and pencils sharpened, please.

For those students who are new this term, let me introduce myself. My name is Keynes — no no, say it like canes — yes, that's good — and I am a professor of economics here at Cambridge.

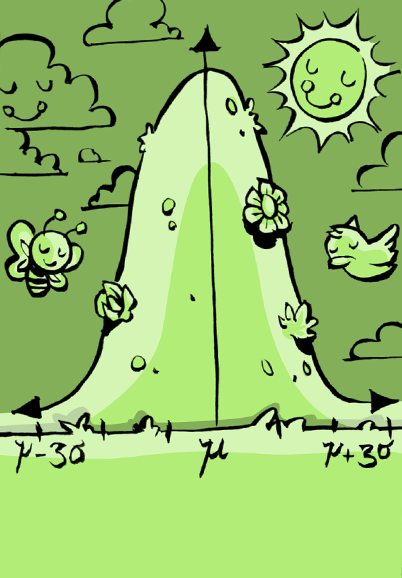

Before I came along, most people happily thought about money in ways that were — well, let's call them "classical," or pre-modern. But those ideas made as much sense to economies as classical ideas could explain the planets — they didn't! The entrenched policies in my day were, deep down, Newtonian: people assumed that money, even on a big scale, works just fine on its own, and that for any dollar that someone has in their wallet, they'll automatically buy things with it. More than anything else, I tried to make it clear that this was bananas — that it was entirely possible for an economy to hit the brakes because there wasn't enough demand. And it had nothing to do with morals, or molecular harmony, or "the free market." It was just the way macro really works — pure and simple.

At least, it was simple until now. Let's dive in!